L: What if I need the loo?

D: Then go. There’s one at the back of the bus.

L: But lots of men have already used it while we’ve been swerving round corners. It’ll be vile by now.

D: Do you actually need to go?

L: No. But what if I do? Would you go and clean it for me first?

D: I most certainly would not.

L: Oh. But what if I need it?

D: But you don’t. Anyway, we’re nearly at the border.

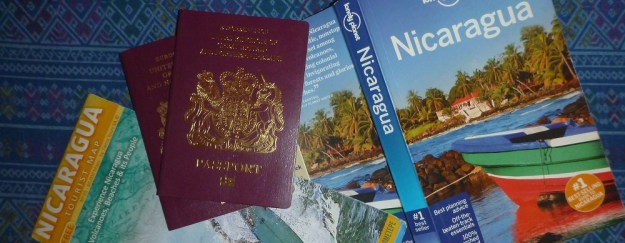

The bus they are on is travelling from Panama through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala to eventually arrive in Mexico three days later. Their journey, however, is only a small segment of this, a mere 8 hours from Costa Rica’s capital, San José, to Granada, on the shores of Lake Nicaragua.

The bus stops at dusk. An announcement is made over the tannoy.

L: Did you get that? What did they say?

D: No idea. We’d better copy everyone else.

They disembark at Peñas Blancas, on the Costa Rican border, clutching passports, completed immigration forms, and receipts for exit taxes collected from all passengers – the tariffs many times higher for tourists than residents. An orderly queue forms, stretching in through the door of a new glass and concrete building.

L: Blimey – how long is this going to take? Some people seem to have been here for days!

Next to the building is a cluster of tents, people dozing on benches, children milling about, and women hanging out laundry on washing lines.

D: That’s the Cubans.

L: What Cubans?

D: Cubans trying to get into the US.

L: So what are they doing here?

D: Nicaragua won’t let them through. They’re stuck.

L: But Cuba’s next door to the US. About 1000 miles north of here. Why on earth are they all the way down here?

D: Lots of Cubans fly to Ecuador and then travel 5000 miles overland back up through South and Central America, rather than risk the incredibly dangerous 90 mile crossing of the shark infested Florida Straits on an overloaded homemade raft.

L: Right.

D: And there’s the wet foot-dry foot policy.

L: The what?

D: The US have an extraordinary policy – if a Cuban can get into the country, they can stay. But only if they have dry feet – if they arrive overland. If they come by boat, the US can still turn them away in US waters, before they get ashore.

L: OK……. But why go all the way down to Ecuador?

D: Direct flights from Havana and no visas needed. It’s hellishly difficult though. First most of them get robbed of their life savings in Colombia. Then they pay through the nose to get into Panama in one piece – seeing as most of the land on the border is full of impenetrable jungles and swamps and gangs with machine guns that are best avoided. And now they’re stuck here.

L: Why won’t Nicaragua let them through?

D: It’s political. They’re generally a bit touchy about their borders with Costa Rica, and Nicaragua also has a lot of Communist history with Cuba. I found an interesting article about it. You should read it. Here.

L: Thanks. I will. What makes them leave Cuba in the first place? To make all this worthwhile?

D: Poverty. Lack of opportunity. Temptation of all things golden just across the water in Miami. Following family. Read the article.

L: I will. So what’s going to happen to these people? They’re not even half way.

D: All the countries between here and the US, except Nicaragua, are rallying round to get them moving again. They won’t be here for ever, but it’ll take some time. There’s 8,000 of them waiting. Read the article!

L: I will! But not now – look, our turn next.

The queue moves, they reach the front and, unlike the beleaguered Cubans, have their passports swiftly stamped, and get back on the bus.

The bus drives on. For 500 metres. And then stops again. An announcement is made over the tannoy.

L: Did you get that? What did they say?

D: No idea. Just copy everyone else. This must be the Nicaraguan border.

They hand over entry taxes to their bus driver, along with their passports. He disappears. This time everyone removes all their hand luggage from the bus, and their suitcases from the hold. They stand around in a hot dusty car park. It gets properly dark. A man tries to sell them a hammock. They stand some more. Money-changers circulate, fanning 4-inch thick wads of cash.

L: Are you excited?

D: About getting back on the bus?

L: About being in Nicaragua.

D: What’s everyone waiting for?

L: It’s got 28 volcanoes.

D: Good. I might ask someone.

L: And the largest lake in Central America.

D: Great. I can’t see anyone to ask.

Eventually a couple of officials are spotted wearing blue T-shirts and carrying clipboards. The crowd drifts towards the officials, dragging their bags until they are all standing on a large raised platform, as though waiting for a train. Lollipop sellers weave through the melee, men with baskets on their heads brimming with cigarettes, women selling leather goods: belts and wallets. There are no counters, no instructions, no clues. They stand around. The T-shirts with clipboards are passing randomly from one traveller to the next.

L: And there’s wonderful Spanish architecture, dating back to the 16th century.

D: I want to join a queue.

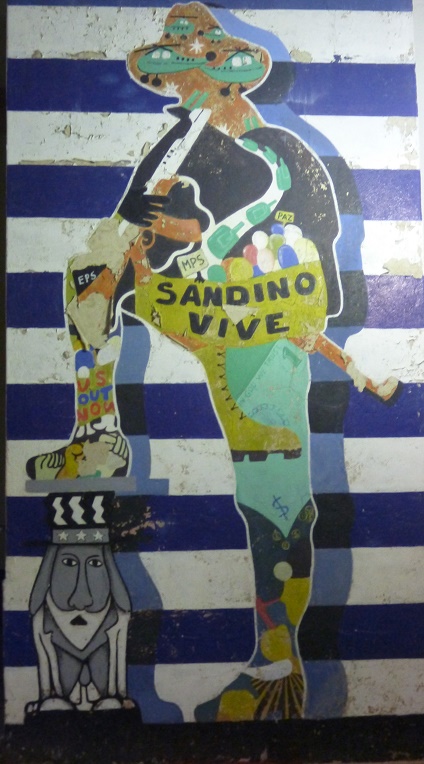

L: There isn’t one. And they had a revolution.

D: What, in the 16th century?

L: No, in the 1970s. Which ended a 40 year dictatorship but left the country massively in debt.

D: I’m miserable. Don’t they understand the British are only happy when queuing?

L: It’s the poorest country in the Americas.

D: Right. Shall I start a queue? Stand behind me.

L: But they’re on the up. They reckon they’re about half way through a 50 year economic recovery. You’re not actually listening, are you?

They spot a Clipboard riffling through a suitcase on a wooden workbench, and shuffle towards him. Another Clipboard approaches from behind. He gives D’s rucksack a brief squeeze.

Clipboard: Clothes?

D: Yes.

Clipboard: OK.

He inclines his head, suggesting that they are now free to leave the platform. They haul their luggage back to the bus, which is locked. They stand around. They buy lollipops. They wait. The bus driver opens the hold and the passengers surge forward. He is impatient.

Driver: Managuamanaguamanagua!

Some passengers are waved forward, others have their luggage rejected. They wait.

Driver: Granadagranadagranada!

D: Granada – that’s us. He’s shouting the destinations and grouping the bags together.

They hand over their backpacks. At the bus door, the crowd regroups, and a uniformed female calls out names. People push through, take the proffered passport and board the bus. They wait. D’s name is called. He claims his passport and returns to L. They wait. The woman is cross. She waves a passport.

Woman: Honey. Honey?

No-one steps forward.

Woman: Honey?

L: Maybe that’s me.

D: That sounds nothing whatsoever like you. Why would she call you honey?

L: Maybe she’s saying “Jane”. In Spanish. My middle name.

D: That’s really quite a big stretch. But we can go and check.

L steps forward and reclaims her passport. The woman gives her a long, weary look, for being stupid, and foreign.

Two hours after disembarking, they get back on the bus.

D: Well, that was all fairly straightforward, wasn’t it?

They see nothing of Nicaragua beyond the windows of the bus, until they pass through the small town of Rivas. An important baseball game has just been won. Everyone is out in the streets, thronging both sides of the main road. Hundreds of vuvuzelas are crowing triumphantly and scooters and motorbikes buzz to and fro, carrying pairs of youths or whole families, bare-legged children wedged between parents. Bicycles weave through the crowd, with passengers perched on crossbars or handlebars, some with toddlers tucked under one arm.

In Granada they are left in a dark scruffy side street. No other tourists get off.

L: We need a taxi. A proper licensed one. The fare should be two dollars, but they’ll ask for five. Let me do the talking.

They approach a battered looking vehicle. It’s the only taxi in sight.

L: How much to the city centre?

Driver: Ten dollars.

L: Oh. How about five?

Driver: (looking resigned): OK.

D: Neatly done. I am impressed. You really told him.

L: Shut up.

They are driven through a grid of deserted streets. The buildings are low, just one or two storeys, colonial in style, all peeling ochre paint and wrought iron window grills.

L: We’re staying right in the centre so that we can walk everywhere easily. Accommodation in Nicaragua’s a lot cheaper than Costa Rica.

D: Great – so we’re saving some money.

L: Err…no. I just spent the same amount as I would in Costa Rica, but got a much nicer hotel.

They are dropped outside a large and pretty colonial building on a pedestrian street. Inside, beyond the reception desk, terracotta roofs enclose a beautiful central courtyard, with porticos, greenery and a fountain. They walk up creaking highly polished wooden stairs to a wide open balcony overlooking the courtyard, off which open several pairs of immense double doors.

L: Here we are.

Their room is high ceilinged with parquet flooring, and a large bathroom. At the far end of the room is another set of double doors.

L: I booked one with a balcony. Apparently it’s got a volcano view.

She throws open the doors and steps out, leaning over the stone balustrade. D comes out of the bathroom, looking alarmed.

D: What the hell is going on?

A great wave of noise washes into the room. Below them is the pedestrian street. It is lively. A dozen restaurants have outdoor seating, crowded with diners, all talking and laughing. A cacophony of music drifts out from the interiors, mixing not altogether harmoniously in the street. Directly opposite their window is the proud green sign of an “Irish Pub”, music and drinkers overflowing out of the door. Street vendors sell jewellery, drinks and snacks, lottery tickets, and song-stones of painted birds, all shouting out their wares. A pair of traditional dancers performs to the beat of a drum, whirling and clapping, before moving on. Pedestrians and cyclists amble up and down, chatting and eating ice creams. Children run shrieking, chasing a puppy. A group of acrobatic breakdancing kids set up, beatbox booming, spinning on their heads and contorting impressively. A mariachi band pass by, a trumpet solo soaring up to their balcony.

L: I’m afraid I might have booked the noisiest room in town.

D: You think?

L: But it’s fantastic for people watching. It’s all happening, right here, under our balcony.

D: Yes. It certainly is.

Later….

L: Are you awake?

D: No.

L: I wonder how soon it’ll quieten down?

D: Go to sleep.

Much later…..

D: Why don’t you shut the windows?

L: They are shut.

D: I hate mariachi. Go and tell them to leave me alone.

L: You do it.

D: I can’t. I’m asleep.

Much, much later….

D: That bloody trumpet! What time is it?

L: 4.17am.

A line of ponies and traps stretch along one edge, waiting calmly for tourists seeking a city-tour circuit. The ponies seem painfully thin. Beyond the plaza, shop keepers are opening up, washing down pavements, bringing out displays. Further still, paintwork turns faded and streets residential. Doorways secured by wrought iron gates open into elegant parlours with bright polished floors, rocking chairs and low tables, beyond which are glimpses of green courtyard gardens. As the day warms up, occupants rest in the cool dark interiors, and rock, eased by the through breeze between courtyard and street.

A line of ponies and traps stretch along one edge, waiting calmly for tourists seeking a city-tour circuit. The ponies seem painfully thin. Beyond the plaza, shop keepers are opening up, washing down pavements, bringing out displays. Further still, paintwork turns faded and streets residential. Doorways secured by wrought iron gates open into elegant parlours with bright polished floors, rocking chairs and low tables, beyond which are glimpses of green courtyard gardens. As the day warms up, occupants rest in the cool dark interiors, and rock, eased by the through breeze between courtyard and street. They walk the increasingly hot kilometre back towards the centre. At the Iglesia de La Merced there is a service going on. The large space is filled with people, standing and sitting and milling and singing. They climb the narrow winding staircase to the top of the bell tower. Views stretch in all directions, across terracotta town roofs, to the lake, to hills and volcanoes and green wooded plains.

They walk the increasingly hot kilometre back towards the centre. At the Iglesia de La Merced there is a service going on. The large space is filled with people, standing and sitting and milling and singing. They climb the narrow winding staircase to the top of the bell tower. Views stretch in all directions, across terracotta town roofs, to the lake, to hills and volcanoes and green wooded plains.

In the afternoon they take a boat around Las Isletas, several hundred tiny tree-covered volcanic islands scattered just offshore. Some are uninhabited, while others have just one property – their own little kingdoms. D admires the gardens, the quays and the varied architecture.

In the afternoon they take a boat around Las Isletas, several hundred tiny tree-covered volcanic islands scattered just offshore. Some are uninhabited, while others have just one property – their own little kingdoms. D admires the gardens, the quays and the varied architecture. Ramon nods happily at this. He has cheered right up. The sun sparkles on the water, which is murky but clean. They spot egrets, herons, ospreys. In the distance is the craggy backdrop of Volcan Mombacho.

Ramon nods happily at this. He has cheered right up. The sun sparkles on the water, which is murky but clean. They spot egrets, herons, ospreys. In the distance is the craggy backdrop of Volcan Mombacho. They pass another, even grander.

They pass another, even grander. Ramon: There are local people on the islands too. Some of them live as they always have, and some look after the houses of others – the foreigners are a good source of income. A few of the islands can be rented for a night or a week, by tourists.

Ramon: There are local people on the islands too. Some of them live as they always have, and some look after the houses of others – the foreigners are a good source of income. A few of the islands can be rented for a night or a week, by tourists. A rowing boat makes its way slowly along, close to the shore, heavily laden with wood.

A rowing boat makes its way slowly along, close to the shore, heavily laden with wood.

They about turn and, heeding the advice, leave the residential street behind and instead take a parallel route on a busy main road lined with electrical and clothing shops. After a kilometre or so, they reach the distinctive Gothic-fortress style walls of the Mercado de Artesanias. Inside, a hundred dark little stores and stalls are crammed with Nicaraguan craftwork, each merging into the next. There are hammocks and hats, handbags and jewellery, paintings and weavings, leather goods and woodcraft, and a multitude of ceramics. They are greeted but not pursued by stall holders, left to wander calmly through the maze. At 10.30 in the morning, there are no other tourists. They have the place entirely to themselves.

They about turn and, heeding the advice, leave the residential street behind and instead take a parallel route on a busy main road lined with electrical and clothing shops. After a kilometre or so, they reach the distinctive Gothic-fortress style walls of the Mercado de Artesanias. Inside, a hundred dark little stores and stalls are crammed with Nicaraguan craftwork, each merging into the next. There are hammocks and hats, handbags and jewellery, paintings and weavings, leather goods and woodcraft, and a multitude of ceramics. They are greeted but not pursued by stall holders, left to wander calmly through the maze. At 10.30 in the morning, there are no other tourists. They have the place entirely to themselves. The buildings peter out at a sweep of gravel. To the right is the town baseball stadium, to the left a couple of restaurants, quiet at this time of day, and an empty playground. Ahead is the lake, view framed by slender trees, bare during this time of tropical winter, dry leaves crunching underfoot. A walkway and a sun-bleached balustrade provide perches for half a dozen couples, their backs to the view, entwined. Graffiti speckles peeling paintwork – declarations of loves past and present.

The buildings peter out at a sweep of gravel. To the right is the town baseball stadium, to the left a couple of restaurants, quiet at this time of day, and an empty playground. Ahead is the lake, view framed by slender trees, bare during this time of tropical winter, dry leaves crunching underfoot. A walkway and a sun-bleached balustrade provide perches for half a dozen couples, their backs to the view, entwined. Graffiti speckles peeling paintwork – declarations of loves past and present. A punishingly steep paved road drops from the lip of the crater to the lake shore. There is a small charge for vehicle access but pedestrians may enter freely. At the bottom, a pretty lane meanders its way along the shore, shaded by trees, giving glimpses of deep blue water and lighter blue sky between vivid green leaves. There are half a dozen discreet hotels and hostels tucked away, a few luxury villas, and some locally owned shacks, each with their own little piece of waterfront heaven. There are no shops, no bank, and not much public waterfront access. Visitors can pay a day-rate to enjoy the low key facilities of one of the hotels – a shaded beach chair, a wooden dock to swim from, a stretch of sharp volcanic shingle beach, towels, bar, restaurant, restrooms. Some have kayaks.

A punishingly steep paved road drops from the lip of the crater to the lake shore. There is a small charge for vehicle access but pedestrians may enter freely. At the bottom, a pretty lane meanders its way along the shore, shaded by trees, giving glimpses of deep blue water and lighter blue sky between vivid green leaves. There are half a dozen discreet hotels and hostels tucked away, a few luxury villas, and some locally owned shacks, each with their own little piece of waterfront heaven. There are no shops, no bank, and not much public waterfront access. Visitors can pay a day-rate to enjoy the low key facilities of one of the hotels – a shaded beach chair, a wooden dock to swim from, a stretch of sharp volcanic shingle beach, towels, bar, restaurant, restrooms. Some have kayaks. If you get a chance to visit Volcan Mombacho, do. I think you’d like it.

If you get a chance to visit Volcan Mombacho, do. I think you’d like it.

L: D’you know what it all means?

L: D’you know what it all means? Leon’s streets are alive. There are bursts of colour wherever they look. Long vistas down cable-crossed streets, to crumbling churches with Baroque pillars and portals, glowing cream and golden and pink, and the dark peaks of volcanoes against the sharp blue sky. Dazzling bougainvillea overflows walls, and ripe fruit, for sale on the street, overflows baskets and crates: pineapples, persimmon, plums, apples, bananas, melons and limes.

Leon’s streets are alive. There are bursts of colour wherever they look. Long vistas down cable-crossed streets, to crumbling churches with Baroque pillars and portals, glowing cream and golden and pink, and the dark peaks of volcanoes against the sharp blue sky. Dazzling bougainvillea overflows walls, and ripe fruit, for sale on the street, overflows baskets and crates: pineapples, persimmon, plums, apples, bananas, melons and limes. In a quiet, sleepy side street, an ivy-walled courtyard hosts a medical clinic. And, humbly, in one corner, is the understated Gallery of Heroes and Martyrs. Here are displayed 300 small portraits, photographs of earnest-faced teenagers killed in 1978 and 79, resistance fighters for the revolution. The museum is free, and was set up their mothers. On the wall is a quote:

In a quiet, sleepy side street, an ivy-walled courtyard hosts a medical clinic. And, humbly, in one corner, is the understated Gallery of Heroes and Martyrs. Here are displayed 300 small portraits, photographs of earnest-faced teenagers killed in 1978 and 79, resistance fighters for the revolution. The museum is free, and was set up their mothers. On the wall is a quote: L: ….. Ronald Reagan sitting on someone’s head. What’s going on?

L: ….. Ronald Reagan sitting on someone’s head. What’s going on?

They are crossing Leon’s central plaza, where the figure, in her rainbow striped dress, stands the full height of the two storey municipal building running along one side of the square.

They are crossing Leon’s central plaza, where the figure, in her rainbow striped dress, stands the full height of the two storey municipal building running along one side of the square.

D: Let me check. Oh – he’s not a fine fellow. He’s called Arrechavala and he was vile. Now he’s a ghost. You should be looking a bit more terrified.

D: Let me check. Oh – he’s not a fine fellow. He’s called Arrechavala and he was vile. Now he’s a ghost. You should be looking a bit more terrified. L: Yikes – is this the Grim Reaper? This one does look terrifying – quite nightmarish. What’s going on?

L: Yikes – is this the Grim Reaper? This one does look terrifying – quite nightmarish. What’s going on?

The minibus is full. Every seat is taken and the roof is piled high with rucksacks and surfboards. It is heading south from the city of Leon, through flat dry landscapes reminiscent of Australian outback, towards Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific surfing town of San Juan del Sur.

The minibus is full. Every seat is taken and the roof is piled high with rucksacks and surfboards. It is heading south from the city of Leon, through flat dry landscapes reminiscent of Australian outback, towards Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific surfing town of San Juan del Sur. The American: She can get lively from time to time.

The American: She can get lively from time to time.

They disembark and find a taxi. The driver gives them a map of the island. There is one road, shaped like a pair of spectacles, circling the foot of the two volcanoes and joining up in the middle. Two thirds of it is unpaved. The landscape is stunning – the volcanic soil rich and fertile. Lush green pastures, woods and plantain groves spread like skirts around the bare cone of Volcan Concepción, whilst lower Volcan Maderas rises as a thickly wooded clump of peaks and ridges and gullies. Along the road, vivid splashes of bougainvillea tumble over garden fences.

They disembark and find a taxi. The driver gives them a map of the island. There is one road, shaped like a pair of spectacles, circling the foot of the two volcanoes and joining up in the middle. Two thirds of it is unpaved. The landscape is stunning – the volcanic soil rich and fertile. Lush green pastures, woods and plantain groves spread like skirts around the bare cone of Volcan Concepción, whilst lower Volcan Maderas rises as a thickly wooded clump of peaks and ridges and gullies. Along the road, vivid splashes of bougainvillea tumble over garden fences.  Houses are of brightly painted breezeblock, or brick, or wood, with corrugated iron roofs. Sun glints off the clean waters of the lake whose shores include long swathes of sandy beach. The taxi slows frequently, easing across drainage ditches and speed bumps. The traffic is heavy – there are mopeds and bicycles, there are pedestrians, families, children, and men carrying huge tree branches home for fuel. There are chickens, and dogs, and cows, and horses and pigs. There are almost no other cars.

Houses are of brightly painted breezeblock, or brick, or wood, with corrugated iron roofs. Sun glints off the clean waters of the lake whose shores include long swathes of sandy beach. The taxi slows frequently, easing across drainage ditches and speed bumps. The traffic is heavy – there are mopeds and bicycles, there are pedestrians, families, children, and men carrying huge tree branches home for fuel. There are chickens, and dogs, and cows, and horses and pigs. There are almost no other cars. The water is cool, clear and blue. Families sit around the edge, in or out of the water, picnicking and drinking pipa fria through straws – cold coconut water straight from the shell. A few swim solemn lengths. At one end is a tightrope – teenagers wobble and flail for seconds before crashing headlong into the water. At the other end is a rope swing. Fathers and sons climb into a tree, launch themselves out over the pool and let go. The boys flip and somersault to cheers and applause, the men hit the water heavily, swamping those at the edge who squeal in delighted protest.

The water is cool, clear and blue. Families sit around the edge, in or out of the water, picnicking and drinking pipa fria through straws – cold coconut water straight from the shell. A few swim solemn lengths. At one end is a tightrope – teenagers wobble and flail for seconds before crashing headlong into the water. At the other end is a rope swing. Fathers and sons climb into a tree, launch themselves out over the pool and let go. The boys flip and somersault to cheers and applause, the men hit the water heavily, swamping those at the edge who squeal in delighted protest. They walk on, distracted from their search by trees dangling breadfruit, gourds, cocoa pods and other exotic mysteries. D looks sceptically at a lively looking fellow with his stone-carved hair on end and a monkey at his side.

They walk on, distracted from their search by trees dangling breadfruit, gourds, cocoa pods and other exotic mysteries. D looks sceptically at a lively looking fellow with his stone-carved hair on end and a monkey at his side. D: Humph. Oh, come over here. This’s more like it!

D: Humph. Oh, come over here. This’s more like it!

L: Does everyone get their drinking water from the lake?

L: Does everyone get their drinking water from the lake?

Just around the next corner they arrive. The San Ramon Waterfall cascades down the mountain from 40 metres above, ending in a shallow pool. It is so tall and so sheer that they have to tilt their heads backwards, further and further, necks cricking, just to see the top. Moss and tiny ferns line the cliff wall and wet rock glistens in the sunlight. They have the place entirely to themselves, like one big awesome secret. They stand under the waterfall happily, wade in the pool and admire. They sit on a rock, drying off and eating biscuits. Soon a woman arrives with her son, aged about ten. The secret’s out. It’s time to leave.

Just around the next corner they arrive. The San Ramon Waterfall cascades down the mountain from 40 metres above, ending in a shallow pool. It is so tall and so sheer that they have to tilt their heads backwards, further and further, necks cricking, just to see the top. Moss and tiny ferns line the cliff wall and wet rock glistens in the sunlight. They have the place entirely to themselves, like one big awesome secret. They stand under the waterfall happily, wade in the pool and admire. They sit on a rock, drying off and eating biscuits. Soon a woman arrives with her son, aged about ten. The secret’s out. It’s time to leave. They are kayaking along the lakeshore. Women stand in the shallows doing their laundry on rock platforms built for the purpose. Toddlers play on the shore. A fisherman sits on the gunwale of his boat, mending nets. From time to time a rustic wooden dwelling is visible amongst a clump of palm trees at the water’s edge. But mostly the shore is given over to forest and pastures. They spot herons, kingfishers, egrets and ospreys.

They are kayaking along the lakeshore. Women stand in the shallows doing their laundry on rock platforms built for the purpose. Toddlers play on the shore. A fisherman sits on the gunwale of his boat, mending nets. From time to time a rustic wooden dwelling is visible amongst a clump of palm trees at the water’s edge. But mostly the shore is given over to forest and pastures. They spot herons, kingfishers, egrets and ospreys. Guide: Look, a great egret, and next to him a great blue heron.

Guide: Look, a great egret, and next to him a great blue heron. L: Take a photo!

L: Take a photo! Guide: On the bank. Black necked stilt birds.

Guide: On the bank. Black necked stilt birds.