Gokyo (4790m) – Gokyo Ri (5360m) – Sacred Lakes (4990m) – Gokyo (4790m) – Tagnag (4700m)

Date = 23-25 March

L&D are contemplating getting out of bed. The inside of their bedroom window is thickly crusted with ice.

L: So?

D: Minus 1°C.

L: We’re beginning to smell. If only it were 20 degrees warmer, I might wash.

D: What’s your problem? We’ve got hot water on tap!

L: (face lighting up) Really?

D: Almost. We can share a pint of not-quite-cold water from your last-night’s-hot-water-bottle.

L: (face falling) Oh. Ingenious. Great.

In the lodge kitchen, their breath forms great billowing clouds. It’s a race to eat their porridge before it gets cold. Outside the open door a gaggle of fat stripy-bellied snowcocks peck at a handful of scraps.

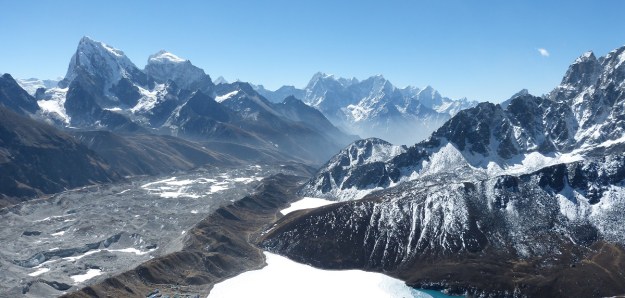

The path from Gokyo up Gokyo Ri’s open south-east slope is entirely in the sun. There’s no wind and not a cloud to be seen. The trail zigs steeply, left and right, up and up. The higher they get, the deeper blue the sky becomes and the more phenomenal the views. The surface of the lake is a dazzling carpet of purest white, encircled by dark rocky crags. The village cowers coldly in the shadow of the glacier wall. As they climb, the terrain morphs to rock and loose stone underfoot. Above 5000m almost no plant life can grow. They pause and turn again, and the view has changed, become more three-dimensional. Behind the mountains there are mountains, and behind the glacier wall is the great Ngozumba Glacier, pushing its way down from the flanks of Cho Oyu.

L: (squeaking with excitement and breathlessness) Look at that – it’s enormous!

L: (squeaking with excitement and breathlessness) Look at that – it’s enormous!

D: It’s supposed to be the longest glacier in the Himalayas.

L: How long?

D: Over 30 kilometres, and a kilometre wide.

L: Why’s it made of rocks? I thought glaciers were ice.

D: The ice is just underneath the surface. Because it’s moving it churns up the stony surface as it goes – especially at the edges – that’s why you’ve got that big ridge between the glacier and the village.

L: And we’ve got to cross it?

D: Not today.

They eye up the glacier’s choppy surface – a rough river of rocky peaks and troughs and pools of ice.

L: Is it safe? Will we fall in a crevasse?

D: No idea. We’ll follow Angtu.

Angu’s reassurances are somewhat ambiguous.

Angtu: We will see. The path changes every time. Not so easy. But not so hard.

On they go. Up and up. Phurba and Angtu laugh and chat in Nepali, Angtu’s conversation punctuated with noisy groans, Phurba’s with duck-quacks.

It takes two hours to reach the top, and for a time they have the place to themselves. The summit ridge of Gokyo Ri is draped with swathes of prayer flags, looped from rock to rock. The 360° views are breath-taking. Behind the glacier, beyond a series of peaks, is the black pyramid of Everest rising clear above the rest.

Angtu: From here you can see 4 of the world’s 10 highest mountains

L: Really? So – Everest. What else?

Angtu: Look to the right a bit. That’s Lhotse – 4th highest. Right a bit more – that’s Makalu, number 5. And then Cho Oyu at the head of the glacier – number 6.

D&L scramble and explore and take photos. They ceremoniously secure their tiny string of prayer-flags and imagine the prayers taking flight, like leaves, spinning and drifting across the magnificent scenery, spreading peace and wisdom, compassion and strength onto the world below. Then they just sit. And look. And take it all in.

D&L scramble and explore and take photos. They ceremoniously secure their tiny string of prayer-flags and imagine the prayers taking flight, like leaves, spinning and drifting across the magnificent scenery, spreading peace and wisdom, compassion and strength onto the world below. Then they just sit. And look. And take it all in.

Angtu and Phurba do the same.

They share biscuits, in companionable silence, sprinkling crumbs for a troupe of canny little high-altitude sparrows who have sussed this inhospitable spot as a daily source of biscuit-eaters.

They notice they haven’t noticed the altitude. They’re at 5360 metres and they feel fantastic. The recent series of short days and height gains have paid off.

The descent takes an hour and a half. Back in their lodge, in a bucket of hot water, they wash their hair, then their bodies and then their clothes. It’s still only lunchtime.

L: We’ve got too much time.

D: For what?

L: We could be doing longer days. Walking further.

D: Who are you? Where’s my proper wife?

L: OK – we’ve got a lovely leisurely itinerary, plenty of time before our flight back to Kathmandu. But we don’t need to be walking short days any more. We’re acclimatised. We’re fit. It’s way too cold to sit around indoors reading or outdoors having picnics and looking at stuff. The only warm place is in bed. And we don’t need the rest.

D: I agree. What shall we do?

L: More walking.

D: Good. I’m going up to the glacier. Are you coming?

L: No way. I’m going to bed.

***

L: I’ve got a headache. I’ve had it all night. Am I going to die?

D: Are you dizzy?

L: No.

D: Sick?

L: No.

D: Confused and irrational?

L: No more than usual.

D: Grumpy?

L: Not sure. Am I?

D: No more than usual.

L: Thanks.

D: Hungry?

L: Yes.

D: You’re not going to die. You’re probably dehydrated. Have a drink.

The dining room is sub-zero. Muffled in thick down jackets and hats they warm their fingers on rapidly cooling mugs of tea.

L: What’s that noise?

D: The rumbling? An aircraft? An avalanche?

L: And booming.

D: Must be building work.

They pack peanut-butter chapati sandwiches for lunch and set off along the flat valley floor on a wide sandy path.

L: Fabulous easy walking Angtu!

Angtu says nothing.

The terrain becomes more and more uneven, littered with stone, rocks, boulders. They pass the fourth sacred lake, a blank ice sheet against a barren brown hillside and cloudless cobalt sky.

The terrain becomes more and more uneven, littered with stone, rocks, boulders. They pass the fourth sacred lake, a blank ice sheet against a barren brown hillside and cloudless cobalt sky.

D: This one’s the deepest. 62 metres.

Angtu: When the ice melts, these lakes are very clean. The water’s very clear – good to drink. No algae grows – it’s too cold.

D: It would be – I think they’re the highest chain of lakes on the planet.

Angtu leads them upwards, and they work their way along the top of the glacier wall, the ground now paved entirely with boulders. They rock-hop from one to the next, carefully. It’s high-concentration, energy-draining stuff. It’s L’s least favourite thing. Angtu moves easily, further ahead, oblivious.

L: I’m going to break all my legs.

D: Slow down then.

L: But we’ll get left behind. Lost in the wilderness.

D: I know where we are.

L: Find me a path.

D: This is a path.

L: This isn’t a path. It’s just stupid rocks. I want a proper path.

D: I think you’ve got symptoms.

L: What of? My headache’s gone.

D: You may be irrational. You’re certainly grumpy. It could be the altitude. Or it could be just you.

The glacier is forbidding up close, an apocalyptic moonscape of slow moving rock and ice, and unfathomably huge. From the flank of Cho Oyu it descends in a blue-white ice-fall, turning to stone as it reaches the floor, carving out a great grey gravel lake before creeping southwards along the valley to Gokyo and beyond.

The glacier is forbidding up close, an apocalyptic moonscape of slow moving rock and ice, and unfathomably huge. From the flank of Cho Oyu it descends in a blue-white ice-fall, turning to stone as it reaches the floor, carving out a great grey gravel lake before creeping southwards along the valley to Gokyo and beyond.

The trail leads close to the edge.

Angtu: Go back! Not this way. The path has fallen into the glacier!

They climb up the steep shoulder and down the other side, to a sandy valley and grassy slope.

L: A lovely proper path!

L cheers up considerably. Her symptoms recede.

Angtu stops and sits down. Points. There, across the valley, behind a couple of low rocky hummocks, is Everest. Not just the summit, but the whole West Face.

L: It’s so close! It’s just there.

Angtu: This is the best view. We’re very lucky with the weather. Very clear today. Mother of the Universe.

L: Mother…?

Angtu: Sagarmatha. The Nepali name. It means Mother of the Universe. Tibetan people have another name for it – Chomolungma. Mother Goddess of the Snows.

An hour further on they arrive at the fifth sacred lake, hidden behind a ridge. They climb to a viewpoint but are buffeted by a bitter wind, and retreat into a sunny dip, where they shelter behind a boulder and eat chapati sandwiches.

L: You know I said more walking?

D: Yes?

L: I’m knackered. And we’ve got to walk all the way back.

Angtu: So, shall we go? Slowly slowly? On to lake 6?

D: I think this is far enough. Thank you.

Angtu looks politely resigned. Phurba has continued to lake 6 and has with him Angtu’s lunch. D&L feed him biscuits and make apologetic faces.

The lovely proper path leads them back to Gokyo along the bottom of a sandy wrinkle in the landscape, avoiding the boulders but also the views. The end is in sight.

D: It was good to do both routes.

L: It’s the lake!!!

L: It’s the lake!!!

D: I can see it’s the lake. We’re nearly back.

L: No – it’s the lake making the noises we heard!

They stop near the edge of the village and listen. From under the surface of the ice comes a prolonged eerie rumble. Then a series of loud hollow whumps, bouncing along from one shore to the other. Spring is on its way and the ice is contracting, beginning to melt. It’s the weirdest thing they’ve ever heard. It continues through the afternoon, audible from indoors.

Once again, for warmth and comfort, they are in bed.

L: Am I on fire?

D: Not that I’ve noticed. Why?

L: I can smell burning hair.

D: It’s yak dung. They’ve lit the stove. It must be 5.00pm. Time to get up.

***

At breakfast they are once more enveloped in the fog of their breathing, clutching plastic mugs of tea to thaw numb fingers, gulping porridge while it still retains some heat. Beyond the iced-up window the frozen lake is booming, as though something gigantic under the surface is thumping to get out.

D buys two small packets of tissues and 8 Snickers bars.

L: How much was that?

D: 24 dollars.

L: HOW MUCH?

D: I can’t talk about it. It’s too painful.

L: It HAS all been carried for a week by a yak or a donkey or a porter to get here. If you consider that, it’s remarkable we can get any of this stuff. At any price.

D: Anyway, the Snickers are medicinal.

A brief scramble behind the village brings them once more to the rim of the glacier. Today they’re going in. They look down over the edge. There is a steep slope of loose stone and scree and gravel and dust that they must descend to get into the glacier, in order to cross it. A couple of people are ahead of them, already at the bottom of the slope. They are tiny, ant-like. D&L shake their heads, trying to knock their brains into registering the scale of what they are seeing. There’s a scuffle and a hiss and a puff of dust below. Loose stones are rattling down the slope. D&L start downwards, skidding and sliding. Another flurry of pebbles tumbles across the path ahead.

A brief scramble behind the village brings them once more to the rim of the glacier. Today they’re going in. They look down over the edge. There is a steep slope of loose stone and scree and gravel and dust that they must descend to get into the glacier, in order to cross it. A couple of people are ahead of them, already at the bottom of the slope. They are tiny, ant-like. D&L shake their heads, trying to knock their brains into registering the scale of what they are seeing. There’s a scuffle and a hiss and a puff of dust below. Loose stones are rattling down the slope. D&L start downwards, skidding and sliding. Another flurry of pebbles tumbles across the path ahead.

D pauses to take a photo. Angtu and Phurba say nothing.

L: Don’t stop here, for chrissakes! We’re about to be hit on the head by falling rocks. Swept to our deaths by a landslide. Wiped off this slope and swallowed by the glacier!

D: You’re right. All those things. Sorry. Carry on.

They make it to the bottom and move away from the fall zone. The wall continues to crumble before their eyes, a little bit here, a little bit there. Down on the glacier itself, it’s a bizarre twisted gravel-pit mess. A sea of crumbling mounds and dips and hillocks and hollows spreads before them, as far as the eye can see. A faint serpentine line weaves its way circuitously into the maze. Down low in the craters, they lose all sense of direction. Up high on the hummocks, the choices are bewildering. Angtu sets off confidently. They follow.

L: When did you last walk across it?

Angtu: Maybe six weeks ago? Twice so far this year. But the path changes each time. It moves.

He observes a guide ahead lead his charges down to the right. Angtu veers uphill and left.

D: Err…should we…umm….follow them?

Angtu: That way’s much longer. This is a short cut.

Sure enough, further on they spot the others completing a long loop to cut in behind them.

L: We won.

Angtu looks pleased. They pause for a rest in the middle of the glacier, on a high mound of debris. In every direction is a formidable wasteland and no sight of a clear trail. They are very glad to be being guided.

They continue, dropping down past the edge of a frozen pool of water. On one side rises a vertical wall of multi-layered ice, festooned with icicles and topped with a carpet of rubble. They stare in fascination at the cross section of glacier. A down-stream path leads them eventually to the foot of the moraine wall on the far side. Their exit is a vertical scramble over loose rock and stones and dust, all crumbling and slipping beneath the soles of their boots, until without warning they suddenly burst over the rim onto a grassy plateau. They are out.

They continue, dropping down past the edge of a frozen pool of water. On one side rises a vertical wall of multi-layered ice, festooned with icicles and topped with a carpet of rubble. They stare in fascination at the cross section of glacier. A down-stream path leads them eventually to the foot of the moraine wall on the far side. Their exit is a vertical scramble over loose rock and stones and dust, all crumbling and slipping beneath the soles of their boots, until without warning they suddenly burst over the rim onto a grassy plateau. They are out.

They stride along the flat turfed ground, slaloming around boulders, dwarfed by a soaring black cliff of coarse rock, to Tagnag. Behind the tiny settlement starts the cleft climbing eventually to the Cho La Pass. The five buildings face west, towards the afternoon sun and a stream and a stony parched-turf plateau stretching away to the glacier edge.

The ambitiously named Chola Pass Resort has terraces paved with turf cut from the ground nearby. Four solar kettles glitter blindingly in the bright sun and a pair of women are energetically breaking up an enormous pile of yak dung. Away from the icy lake of Gokyo it feels warmer here, despite being at a similar altitude.

In the evening the dining room is cosy.

L: Look at that!

She is pointing in amazement at the centre of her pizza.

D: What is it?

L: A slice of fresh tomato! At 4,700 metres! In March!

D: It’s a miracle.

They set off at 5.40am. From behind Tagnag, a cleft climbs and widens, the shallow stream turning to ice as they gain altitude. Their fingers and toes become numb with cold. L fumbles to unscrew the lid of her water bottle. The cold air rushes in and the water quickly freezes. The temperature registers as minus 7°C. The sun rises and tantalisingly floods the mountainside above them but does not reach the trail. They reach a first pass of grey shale, at 5100m, then drop down into a huge parched-grass valley sprinkled with boulders. The views are magnificent but they remain in deep shade.

They set off at 5.40am. From behind Tagnag, a cleft climbs and widens, the shallow stream turning to ice as they gain altitude. Their fingers and toes become numb with cold. L fumbles to unscrew the lid of her water bottle. The cold air rushes in and the water quickly freezes. The temperature registers as minus 7°C. The sun rises and tantalisingly floods the mountainside above them but does not reach the trail. They reach a first pass of grey shale, at 5100m, then drop down into a huge parched-grass valley sprinkled with boulders. The views are magnificent but they remain in deep shade. Angtu: It’s better early, like now, before the sun. Later, when the ice melts it can be unstable. Sometimes there are rockfalls.

Angtu: It’s better early, like now, before the sun. Later, when the ice melts it can be unstable. Sometimes there are rockfalls. They sit in the sun at 5420m, feeling happy and healthy, and munching yak-cheese chapati sandwiches and Snickers and watching brightly jacketed ant-like figures making their way up the snowfield towards them.

They sit in the sun at 5420m, feeling happy and healthy, and munching yak-cheese chapati sandwiches and Snickers and watching brightly jacketed ant-like figures making their way up the snowfield towards them. They take off their crampons and negotiate a narrow rocky snow-covered ledge high on one side of a steep valley wall. They should have kept the spikes on. It is icy and slippery underfoot and the fall would be long and uncomfortable. D watches nervously as ahead Angtu holds L’s hand as she skids and trips and wobbles along the path. Angtu leaves her wedged securely between two boulders while he doubles back to help a pair of independent trekkers also unsteady on their feet.

They take off their crampons and negotiate a narrow rocky snow-covered ledge high on one side of a steep valley wall. They should have kept the spikes on. It is icy and slippery underfoot and the fall would be long and uncomfortable. D watches nervously as ahead Angtu holds L’s hand as she skids and trips and wobbles along the path. Angtu leaves her wedged securely between two boulders while he doubles back to help a pair of independent trekkers also unsteady on their feet. On the far side of the valley, they come over a rise and arrive at Dzongla, a small cluster of scruffy corrugated iron farm-like buildings lying in a bleak little bowl. They are tired and hungry but triumphant to have survived despite the dire warnings of ice and falling rocks and crevasses. The lodge is busy but neither clean, warm nor fragrant – its only redeeming feature a beautifully crafted floor-to-ceiling tower of yak-dung in the hallway.

On the far side of the valley, they come over a rise and arrive at Dzongla, a small cluster of scruffy corrugated iron farm-like buildings lying in a bleak little bowl. They are tired and hungry but triumphant to have survived despite the dire warnings of ice and falling rocks and crevasses. The lodge is busy but neither clean, warm nor fragrant – its only redeeming feature a beautifully crafted floor-to-ceiling tower of yak-dung in the hallway.

From the warmth of their sleeping bags, at 6.00am, they check the temperature in their bedroom.

From the warmth of their sleeping bags, at 6.00am, they check the temperature in their bedroom. On a meadow-like spur they stop to admire the views. A woman walks past, driving her three yaks. She is wearing a traditional full-length skirt and headscarf and carrying a high-tech trekking backpack. The river meanders down the valley, back towards Lukla. To their left is an immense dam of glacial rubble – the stony front end of the Khumbu Glacier. At its foot, seemingly right in its path, cower the buildings of Dughla. To their right towers the craggy shoulder of Cholatse. Angtu and Phurba strike poses and photograph each other. Then they sit and eat biscuits.

On a meadow-like spur they stop to admire the views. A woman walks past, driving her three yaks. She is wearing a traditional full-length skirt and headscarf and carrying a high-tech trekking backpack. The river meanders down the valley, back towards Lukla. To their left is an immense dam of glacial rubble – the stony front end of the Khumbu Glacier. At its foot, seemingly right in its path, cower the buildings of Dughla. To their right towers the craggy shoulder of Cholatse. Angtu and Phurba strike poses and photograph each other. Then they sit and eat biscuits. They turn their back on Cholatse to the west and Ama Dablam to the south, and head north towards perfect peak of Pumori. There are only a very few other people on their path, but below them they can see strings of tiny figures zig-zagging their way slowly up from Dughla, climbing the rough tongue of the glacier. This is the main Everest trekking route, and it’s busy.

They turn their back on Cholatse to the west and Ama Dablam to the south, and head north towards perfect peak of Pumori. There are only a very few other people on their path, but below them they can see strings of tiny figures zig-zagging their way slowly up from Dughla, climbing the rough tongue of the glacier. This is the main Everest trekking route, and it’s busy.

In a little barren side valley a solitary low stone lodge is half buried into the hillside and topped by a large glass pyramid sheathed in solar panels. Behind, in a perfect mirror image, rises the white peak of Pumori, and opposite, a glacier tumbles straight down the mountain into the valley. A few dumb-bells and makeshift gym equipment sit on a low wall. They are definitely in the right place.

In a little barren side valley a solitary low stone lodge is half buried into the hillside and topped by a large glass pyramid sheathed in solar panels. Behind, in a perfect mirror image, rises the white peak of Pumori, and opposite, a glacier tumbles straight down the mountain into the valley. A few dumb-bells and makeshift gym equipment sit on a low wall. They are definitely in the right place. Kaji: We also collect geological seismic data – any earthquake activity.

Kaji: We also collect geological seismic data – any earthquake activity.

The bliss ends abruptly as their route converges with the main path at a junction of two glaciers. The meeting point is a monumental mess of rubble and rocks and boulders. It’s less than a kilometre across the glacier to Gorak Shep on the far side, but it takes them an hour. The dusty, stony trail weaves and undulates through the maze. Every step is uneven, the ground loose, and dust rises to coat their faces. New paths are forged as old ones fall away, crushed by slabs of dirty grey ice and dragged underground by slow-moving debris.

The bliss ends abruptly as their route converges with the main path at a junction of two glaciers. The meeting point is a monumental mess of rubble and rocks and boulders. It’s less than a kilometre across the glacier to Gorak Shep on the far side, but it takes them an hour. The dusty, stony trail weaves and undulates through the maze. Every step is uneven, the ground loose, and dust rises to coat their faces. New paths are forged as old ones fall away, crushed by slabs of dirty grey ice and dragged underground by slow-moving debris. They climb the hill, checking their altimeter, breathing heavily but otherwise comfortable, and stop once they’ve reached 100m. From here they can see the Porters’ Lodge. It is set apart from the other buildings – a long low corrugated-iron barn with no windows, but skylights in the roof. It looks a lot like a cow shed.

They climb the hill, checking their altimeter, breathing heavily but otherwise comfortable, and stop once they’ve reached 100m. From here they can see the Porters’ Lodge. It is set apart from the other buildings – a long low corrugated-iron barn with no windows, but skylights in the roof. It looks a lot like a cow shed.

Gorak Shep (5160m) – Everest Base Camp (5364m) – Gorak Shep (5160m)

Gorak Shep (5160m) – Everest Base Camp (5364m) – Gorak Shep (5160m) Instead of starting from Gorak Shep, most guided groups walk for 3 hours from Lobuche, pausing for an early lunch in Gorak Shep before arriving at Everest Base Camp in the early afternoon, and then heading back to Gorak Shep for the night. It saves a day, keeps costs down and reduces the time spent at over 5000m.

Instead of starting from Gorak Shep, most guided groups walk for 3 hours from Lobuche, pausing for an early lunch in Gorak Shep before arriving at Everest Base Camp in the early afternoon, and then heading back to Gorak Shep for the night. It saves a day, keeps costs down and reduces the time spent at over 5000m. They descend onto the Khumbu glacier at around 10am – the landscape a heavy rolling sea of snow-sprinkled rock-strewn peaks and troughs. Ahead a train of yaks weaves its way calmly through the chaos. The path leads them to a small hillock strewn with prayer flags. They are approached by a tall bearded man speaking heavy accented English with some difficulty. D&L they recognise the accent and switch helpfully into Italian.

They descend onto the Khumbu glacier at around 10am – the landscape a heavy rolling sea of snow-sprinkled rock-strewn peaks and troughs. Ahead a train of yaks weaves its way calmly through the chaos. The path leads them to a small hillock strewn with prayer flags. They are approached by a tall bearded man speaking heavy accented English with some difficulty. D&L they recognise the accent and switch helpfully into Italian. They grin at each other stupidly in disbelief. Angtu returns and leads them over to the pile of stones and prayer flags, where he has dusted the snow off a couple of small rocks on which people have written EBC and the date, in crayon. It’s good enough for the Italian. He gets out his camera phone and then delves once more into his rucksack, bringing out a fist-sized rock on which is written “Majella – Abruzzo – Italy”

They grin at each other stupidly in disbelief. Angtu returns and leads them over to the pile of stones and prayer flags, where he has dusted the snow off a couple of small rocks on which people have written EBC and the date, in crayon. It’s good enough for the Italian. He gets out his camera phone and then delves once more into his rucksack, bringing out a fist-sized rock on which is written “Majella – Abruzzo – Italy” He leads them on through Base Camp. On their left, Nepali expedition teams are clearing rocks and carving flat platforms in the ice on which to set up tents. Clusters of tents are already in place, and set apart from the rest are tiny latrine huts balancing on pedestals of ice or rock – a loo seat suspended over a plastic drum. Beside them, sculptural shards of ice thrust upwards through the debris. On their right flows the Khumbu Icefall – close enough to touch and unfathomably huge. Tumbling steeply down from the Western Cwm is a kilometre wide torrent of dazzling house-sized blocks of ice. It’s on the move, flowing at the rate of about a metre a day, constantly shifting and collapsing, opening yawning new crevasses. It’s beautiful and terrifying. Helicopters skim along the glacier, over the camp and back again, providing photo opportunities for non-trekking tourists. The Icefall is so enormous that the little aircraft dip down behind it, lost to sight from where D&L are standing.

He leads them on through Base Camp. On their left, Nepali expedition teams are clearing rocks and carving flat platforms in the ice on which to set up tents. Clusters of tents are already in place, and set apart from the rest are tiny latrine huts balancing on pedestals of ice or rock – a loo seat suspended over a plastic drum. Beside them, sculptural shards of ice thrust upwards through the debris. On their right flows the Khumbu Icefall – close enough to touch and unfathomably huge. Tumbling steeply down from the Western Cwm is a kilometre wide torrent of dazzling house-sized blocks of ice. It’s on the move, flowing at the rate of about a metre a day, constantly shifting and collapsing, opening yawning new crevasses. It’s beautiful and terrifying. Helicopters skim along the glacier, over the camp and back again, providing photo opportunities for non-trekking tourists. The Icefall is so enormous that the little aircraft dip down behind it, lost to sight from where D&L are standing. D: Base Camp was so clean. I thought Everest was notorious for being strewn with rubbish. But it was entirely litter-free.

D: Base Camp was so clean. I thought Everest was notorious for being strewn with rubbish. But it was entirely litter-free.

They leave him to his breakfast and set off. There’s a thin crust of snow, a bitter wind and a leaden grey sky which is slowly shifting and cracking. Without the sun the landscape is monochrome and harsh. There is rock and snow. Black and white. Cold and colder.

They leave him to his breakfast and set off. There’s a thin crust of snow, a bitter wind and a leaden grey sky which is slowly shifting and cracking. Without the sun the landscape is monochrome and harsh. There is rock and snow. Black and white. Cold and colder. D: It’s amazing! Take photos of everything!

D: It’s amazing! Take photos of everything! They set off back to Lobuche. Without the sun to melt the dusting of snow, the landscape stays monochrome and the windchill is biting. Once again they across the chaotic maze of glacial moraine.

They set off back to Lobuche. Without the sun to melt the dusting of snow, the landscape stays monochrome and the windchill is biting. Once again they across the chaotic maze of glacial moraine. A team of yaks, heavily laden with equipment for Everest Base Camp, drink from Lobuche’s stream. A helicopter lands outside the lodge, throwing up a mini blizzard of fine snow which sparkles in the bright sun.

A team of yaks, heavily laden with equipment for Everest Base Camp, drink from Lobuche’s stream. A helicopter lands outside the lodge, throwing up a mini blizzard of fine snow which sparkles in the bright sun. Among them is Scott Fischer, the American mountaineer and guide known for ascending the world’s highest peaks without extra oxygen. In May 1996 he led a group of clients up Everest, assisted by two other guides. After helping others, he summitted Everest late in the day and during his descent was caught in a violent blizzard that took the lives of 8 people, including Fischer. In this spot there is also a memorial to Anatoli Boukreev, a respected Russian Kazakhstani climber and one of Fischer’s fellow guides on that day. After rescuing others, Boukreev did manage to reach Fischer, but he was already dead. Boukreev survived, but was killed in an avalanche while climbing Annapurna 18 months later. One of the largest memorials is to Babu Chiri Sherpa, who climbed Everest 10 times, holding the record for the fastest ascent (under 17 hours), and for the most time on the summit without auxiliary oxygen (21 hours), as well as summitting twice in two weeks. He died on his 11th summit bid of Everest, falling into a deep crevasse in April 2001.

Among them is Scott Fischer, the American mountaineer and guide known for ascending the world’s highest peaks without extra oxygen. In May 1996 he led a group of clients up Everest, assisted by two other guides. After helping others, he summitted Everest late in the day and during his descent was caught in a violent blizzard that took the lives of 8 people, including Fischer. In this spot there is also a memorial to Anatoli Boukreev, a respected Russian Kazakhstani climber and one of Fischer’s fellow guides on that day. After rescuing others, Boukreev did manage to reach Fischer, but he was already dead. Boukreev survived, but was killed in an avalanche while climbing Annapurna 18 months later. One of the largest memorials is to Babu Chiri Sherpa, who climbed Everest 10 times, holding the record for the fastest ascent (under 17 hours), and for the most time on the summit without auxiliary oxygen (21 hours), as well as summitting twice in two weeks. He died on his 11th summit bid of Everest, falling into a deep crevasse in April 2001. Over a rise they look down into the next valley, a steep-sided groove cut by a fast-flowing river. As they drop lower, the vegetation gets taller.

Over a rise they look down into the next valley, a steep-sided groove cut by a fast-flowing river. As they drop lower, the vegetation gets taller. She potters through the door curtain and climbs up onto the bench next to L. They stare at each other for a bit. She puts her face right up to L’s, and laughs. She pokes L. L smiles and pokes her gently back. She giggles and pokes. And giggles and pokes. And giggles. The soup arrives. Her mother shoos her off the bench. The little girl tries to climb out of the window, gives up and disappears back through the curtain. She makes herself busy in the yard throwing cups of water at hens.

She potters through the door curtain and climbs up onto the bench next to L. They stare at each other for a bit. She puts her face right up to L’s, and laughs. She pokes L. L smiles and pokes her gently back. She giggles and pokes. And giggles and pokes. And giggles. The soup arrives. Her mother shoos her off the bench. The little girl tries to climb out of the window, gives up and disappears back through the curtain. She makes herself busy in the yard throwing cups of water at hens. Lodge: The hot water bottles are free. Would you like some?

Lodge: The hot water bottles are free. Would you like some?

They cross the river below the village on a steel bridge strewn with prayer flags, and follow a wide path leading up to an open plateau. The sun streams from behind Ama Dablam’s peak, throwing it into silhouette and making the broad snow-field sparkle. Two other small groups, half a dozen trekkers each, are admiring the views back to Pangboche. L strides away across the plateau.

They cross the river below the village on a steel bridge strewn with prayer flags, and follow a wide path leading up to an open plateau. The sun streams from behind Ama Dablam’s peak, throwing it into silhouette and making the broad snow-field sparkle. Two other small groups, half a dozen trekkers each, are admiring the views back to Pangboche. L strides away across the plateau.

They walk towards the little cluster of expedition tents. A dozen or more people are standing or sitting in a group.

They walk towards the little cluster of expedition tents. A dozen or more people are standing or sitting in a group. L: I do actually. I’d really like to think so. The thing is, this landscape is just so enormous, and the weather and conditions up here are so powerful, that it makes one – well, me anyway – feel very tiny and at the mercy of my surroundings. And if you can’t control your environment, it’s instinctive to want to do all you can to stay on its good side.

L: I do actually. I’d really like to think so. The thing is, this landscape is just so enormous, and the weather and conditions up here are so powerful, that it makes one – well, me anyway – feel very tiny and at the mercy of my surroundings. And if you can’t control your environment, it’s instinctive to want to do all you can to stay on its good side. The way up to the 16thC Pangboche Monastery is lined with mani walls. Lots of them. D&L carefully pass them all to the left. Terraced fields are dotted with neat piles of manure and women are preparing the ground for planting potatoes. Pangboche is the oldest Sherpa village in the region, and this is its oldest monastery.

The way up to the 16thC Pangboche Monastery is lined with mani walls. Lots of them. D&L carefully pass them all to the left. Terraced fields are dotted with neat piles of manure and women are preparing the ground for planting potatoes. Pangboche is the oldest Sherpa village in the region, and this is its oldest monastery.

Despite the bustle outside, the elaborately decorated monastery complex is all but deserted. A dog lies flatly on the warm paving stones and four ponies amble through the grounds. D&L circle the gompa, spinning all the prayer-wheels, and admire the deceptively ancient-looking interior, dating back only to 1993. This monastery, originally founded in 1919, burnt down 70 years later and was carefully rebuilt. There is a beautifully serene Buddha, eyes half closed, meditating on the altar, and a wall of prayer books behind. They study a large painted wood panel.

Despite the bustle outside, the elaborately decorated monastery complex is all but deserted. A dog lies flatly on the warm paving stones and four ponies amble through the grounds. D&L circle the gompa, spinning all the prayer-wheels, and admire the deceptively ancient-looking interior, dating back only to 1993. This monastery, originally founded in 1919, burnt down 70 years later and was carefully rebuilt. There is a beautifully serene Buddha, eyes half closed, meditating on the altar, and a wall of prayer books behind. They study a large painted wood panel. L: Just look at them!

L: Just look at them! Descending from Namche to Lukla, they pass trekkers panting their way up the long ascent. In the valley fruit trees are bursting with white and pink blossom and the vivid green of buckwheat patchworks the fields. Rhododendron trees are in flower. They trail is teeming with trekkers and porters and donkeys and yaks.

Descending from Namche to Lukla, they pass trekkers panting their way up the long ascent. In the valley fruit trees are bursting with white and pink blossom and the vivid green of buckwheat patchworks the fields. Rhododendron trees are in flower. They trail is teeming with trekkers and porters and donkeys and yaks. The day dawns grey. It’s almost the only really overcast morning they’ve had in five weeks.

The day dawns grey. It’s almost the only really overcast morning they’ve had in five weeks. They wait, watching the runway through the window. Helicopters continue to arrive, fill and leave.

They wait, watching the runway through the window. Helicopters continue to arrive, fill and leave. They are back at the airport at 7am. The clouds are swirling, but higher, and the skies are much clearer. Planes arrive and leave. They check in again. Planes arrive. Planes leave. The cloud builds and lowers. The planes stop coming. They wait.

They are back at the airport at 7am. The clouds are swirling, but higher, and the skies are much clearer. Planes arrive and leave. They check in again. Planes arrive. Planes leave. The cloud builds and lowers. The planes stop coming. They wait.