Gorak Shep (5160m) – Everest Base Camp (5364m) – Gorak Shep (5160m)

Gorak Shep (5160m) – Everest Base Camp (5364m) – Gorak Shep (5160m)

Date = 29 March

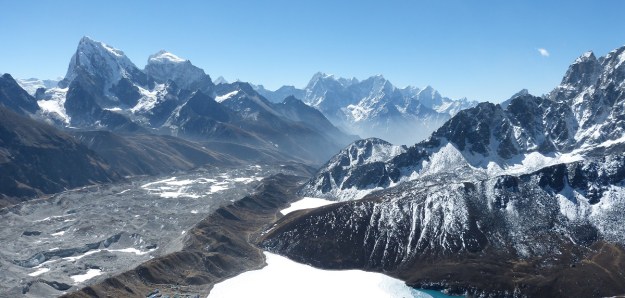

There are two inches of snow on the ground when D&L set off from Gorak Shep for Everest Base Camp, but the going is easy. They wend their way gently up the edge of the Khumbu glacier, the rock and dust beneath their feet covered in clean crunchy snow. The temperature is minus 6°C but the sky is blue and clear, and the sun is warm on their faces. On every horizon white peaks soar skywards. They share the path with few porters and Nepali expedition staff heading for Base Camp, but almost no other trekkers.

The guidebook is unenthusiastic about today’s walk.

“Many people have unrealistic expectations of Base Camp and end up being disappointed….there are no views of Everest…and cloud often rolls down from the peaks, obscuring everything in a grey fog. The main reason to go there is to say you have been there.”

Instead of starting from Gorak Shep, most guided groups walk for 3 hours from Lobuche, pausing for an early lunch in Gorak Shep before arriving at Everest Base Camp in the early afternoon, and then heading back to Gorak Shep for the night. It saves a day, keeps costs down and reduces the time spent at over 5000m.

Instead of starting from Gorak Shep, most guided groups walk for 3 hours from Lobuche, pausing for an early lunch in Gorak Shep before arriving at Everest Base Camp in the early afternoon, and then heading back to Gorak Shep for the night. It saves a day, keeps costs down and reduces the time spent at over 5000m.

L: But it means they’ve walked for 5 hours to get to Base Camp, instead of 2. So everyone’s exhausted.

D: True.

L: And they’ve gained 450 metres in altitude instead of 200. So they’re probably not feeling so great.

D: Also true.

L: And they’ll get to get to Base Camp in the afternoon, after the clouds have built up. So they might not see anything.

D: You’re right. I agree with the guide book. Could be a pretty rubbish sort of day.

They descend onto the Khumbu glacier at around 10am – the landscape a heavy rolling sea of snow-sprinkled rock-strewn peaks and troughs. Ahead a train of yaks weaves its way calmly through the chaos. The path leads them to a small hillock strewn with prayer flags. They are approached by a tall bearded man speaking heavy accented English with some difficulty. D&L they recognise the accent and switch helpfully into Italian.

They descend onto the Khumbu glacier at around 10am – the landscape a heavy rolling sea of snow-sprinkled rock-strewn peaks and troughs. Ahead a train of yaks weaves its way calmly through the chaos. The path leads them to a small hillock strewn with prayer flags. They are approached by a tall bearded man speaking heavy accented English with some difficulty. D&L they recognise the accent and switch helpfully into Italian.

Man: Ahh! You are Italian!

D: No, we’re English.

Man: But you speak Italian!

D: Yes.

Man: Fantastic! So where is the Base Camp?

They confer with Angtu in English.

D: Umm…here, sort of.

Man: But where is the sign?

They confer again with Angtu.

D: Err..there is no sign.

Man: But for my photos. I must have a sign!

They explain to Angtu. The Italian has seen pictures of trekkers posing triumphantly in front of a big yellow sign. And a huge engraved boulder. Angtu shrugs and walks away.

Man: So why d’you speak Italian?

D: We have a house in Italy.

Man: Oh! Where in Italy?

D: Abruzzo.

This is usually the end of the conversation. The relatively unknown region of Abruzzo in central Italy is not on most people’s radar. Except, it seems, for today.

Man: No! It can’t be true. I come from Abruzzo! Where in Abruzzo?

D: The Majella National Park.

Now they will lose him. Almost no-one lives in the beautiful mountains of the Majella, with its harsh winters and lack of jobs. He will live on the coast, in the region’s capital maybe. But no, it seems, he does not. He spreads his arms wide.

Man: Aah! It’s not possible! I come from the Majella!

They grin at each other stupidly in disbelief. Angtu returns and leads them over to the pile of stones and prayer flags, where he has dusted the snow off a couple of small rocks on which people have written EBC and the date, in crayon. It’s good enough for the Italian. He gets out his camera phone and then delves once more into his rucksack, bringing out a fist-sized rock on which is written “Majella – Abruzzo – Italy”

They grin at each other stupidly in disbelief. Angtu returns and leads them over to the pile of stones and prayer flags, where he has dusted the snow off a couple of small rocks on which people have written EBC and the date, in crayon. It’s good enough for the Italian. He gets out his camera phone and then delves once more into his rucksack, bringing out a fist-sized rock on which is written “Majella – Abruzzo – Italy”

Man: Look! I brought this here! To Everest Base Camp! All the way from the Majella! From my mountain! He places it reverently on top of stony pile and photographs it proudly.

L: That’s some dedication. You’re going to make me cry!

He hugs her.

Man: I’m crying a bit too!

They leave him taking hundreds of photos of himself and his trek mates, accessorised with Italian T-shirts, hats and flags. At this point most trekkers stop, take a few selfies, and then retrace their steps. But the expedition tents for those attempting to summit Everest are spread out along the rocky glacier for a mile or so beyond them. L wants to see more.

L: Angtu? Can we go on? Up to where the tents are?

Angtu: This way.

He leads them on through Base Camp. On their left, Nepali expedition teams are clearing rocks and carving flat platforms in the ice on which to set up tents. Clusters of tents are already in place, and set apart from the rest are tiny latrine huts balancing on pedestals of ice or rock – a loo seat suspended over a plastic drum. Beside them, sculptural shards of ice thrust upwards through the debris. On their right flows the Khumbu Icefall – close enough to touch and unfathomably huge. Tumbling steeply down from the Western Cwm is a kilometre wide torrent of dazzling house-sized blocks of ice. It’s on the move, flowing at the rate of about a metre a day, constantly shifting and collapsing, opening yawning new crevasses. It’s beautiful and terrifying. Helicopters skim along the glacier, over the camp and back again, providing photo opportunities for non-trekking tourists. The Icefall is so enormous that the little aircraft dip down behind it, lost to sight from where D&L are standing.

He leads them on through Base Camp. On their left, Nepali expedition teams are clearing rocks and carving flat platforms in the ice on which to set up tents. Clusters of tents are already in place, and set apart from the rest are tiny latrine huts balancing on pedestals of ice or rock – a loo seat suspended over a plastic drum. Beside them, sculptural shards of ice thrust upwards through the debris. On their right flows the Khumbu Icefall – close enough to touch and unfathomably huge. Tumbling steeply down from the Western Cwm is a kilometre wide torrent of dazzling house-sized blocks of ice. It’s on the move, flowing at the rate of about a metre a day, constantly shifting and collapsing, opening yawning new crevasses. It’s beautiful and terrifying. Helicopters skim along the glacier, over the camp and back again, providing photo opportunities for non-trekking tourists. The Icefall is so enormous that the little aircraft dip down behind it, lost to sight from where D&L are standing.

A man emerges from a tent and shouts to Angtu.

L: Are we in trouble? What’s he saying?

Angtu: He’s asking if we’d like some tea.

It’s warm inside the expedition kitchen tent despite the smooth ice floor. Folding tables support large thermoses and cauldrons. Soup is warming on a kerosene stove and a tower of egg boxes stands in a corner. They perch on folding stools, sipping peach tea out of tin mugs and happily pretending they are part of an Everest ascent team.

On the return to Gorak Shep, the trail is now bustling with traffic heading up to Base Camp. Bunches of slow-moving trekkers, strings of high-piled head-swinging yaks, and porters bent double under the weight on their backs. A mountain of mattresses walks by. There’s a guy with a half dozen long steel and wood folding tables. They step aside for a man carrying a large fridge, and for another with a full size cooker. One porter has 4 x 15kg gas bottles on his back. Another is entirely buried under an immense roll of carpet.

D: Base Camp was so clean. I thought Everest was notorious for being strewn with rubbish. But it was entirely litter-free.

D: Base Camp was so clean. I thought Everest was notorious for being strewn with rubbish. But it was entirely litter-free.

Angtu: Base Camp is managed by the SPCC – the National Park pollution control guys. They do a good job. But higher on the mountain it’s a different story.

D: In what way?

Angtu: The SPCC clear up all the rubbish as far as Camp 2, at 6,600 metres, above the Icefall and the Western Cwm. They supply the Icefall Doctors too.

D: The Icefall Doctors?

Angtu: The guys who fix all the ladders through the Icefall at the start of each season. They pick the safest route and put maybe 50 or more ladders across the crevasses. So the climbers can get through it.

D: Sounds dangerous.

Angtu: It is. Very dangerous. Those guys are the real experts.

L: It’s impressive that the SPCC are keeping the mountain clean all the way up to 6,600 metres. That’s some seriously extreme litter picking! Miyolangsangma, goddess protector of Everest, must be happy.

Angtu: No. I think she must be very sad.

L: But why?

Angtu: Further up – above Camp 2 – it gets bad. Very bad. Climbing teams leave a lot of rubbish in the higher camps. Equipment, oxygen bottles, ladders, food wrappers and a lot of toilet waste. Even branded stuff like tents – they just cut their company name off and leave it up there.

D: But don’t they pay a big garbage deposit which they’d lose?

L: Think about it. The deposit’s probably been charged to the client, who won’t be expecting it back. And if it’s easier for the companies to leave stuff up there and not reclaim the deposit, they exert minimum effort and lose nothing. The next client’s fees probably pays for all new equipment.

Angtu: There are supposed to be exit checks. Counting the equipment going up and coming back down. To make sure all waste is removed from the mountain, and so they can return the garbage deposits. But the exit checks aren’t done.

D: Isn’t every expedition member also supposed to bring 8kg of extra waste down with them?

Angtu: Yes. But again – no-one’s checking.

L: That’s so sad. It shouldn’t need to be about checking – it’s about respect and common sense. The companies who come every year are quite literally crapping on their own doorsteps. It’s ludicrous! And the clients – how can they spend months in this most awesomest of landscapes and then have so little respect for it as to leave waste behind? What’s happened to basic human conscience?

D: You’re really shouting now.

Angtu: It’s different up there. The priority is to stay alive. Get to the summit. Get down again. And come home. It’s a problem.

D: And I’m not sure “awesomest” is even a word. Though it should be.

They leave him to his breakfast and set off. There’s a thin crust of snow, a bitter wind and a leaden grey sky which is slowly shifting and cracking. Without the sun the landscape is monochrome and harsh. There is rock and snow. Black and white. Cold and colder.

They leave him to his breakfast and set off. There’s a thin crust of snow, a bitter wind and a leaden grey sky which is slowly shifting and cracking. Without the sun the landscape is monochrome and harsh. There is rock and snow. Black and white. Cold and colder. D: It’s amazing! Take photos of everything!

D: It’s amazing! Take photos of everything! They set off back to Lobuche. Without the sun to melt the dusting of snow, the landscape stays monochrome and the windchill is biting. Once again they across the chaotic maze of glacial moraine.

They set off back to Lobuche. Without the sun to melt the dusting of snow, the landscape stays monochrome and the windchill is biting. Once again they across the chaotic maze of glacial moraine. A team of yaks, heavily laden with equipment for Everest Base Camp, drink from Lobuche’s stream. A helicopter lands outside the lodge, throwing up a mini blizzard of fine snow which sparkles in the bright sun.

A team of yaks, heavily laden with equipment for Everest Base Camp, drink from Lobuche’s stream. A helicopter lands outside the lodge, throwing up a mini blizzard of fine snow which sparkles in the bright sun. Among them is Scott Fischer, the American mountaineer and guide known for ascending the world’s highest peaks without extra oxygen. In May 1996 he led a group of clients up Everest, assisted by two other guides. After helping others, he summitted Everest late in the day and during his descent was caught in a violent blizzard that took the lives of 8 people, including Fischer. In this spot there is also a memorial to Anatoli Boukreev, a respected Russian Kazakhstani climber and one of Fischer’s fellow guides on that day. After rescuing others, Boukreev did manage to reach Fischer, but he was already dead. Boukreev survived, but was killed in an avalanche while climbing Annapurna 18 months later. One of the largest memorials is to Babu Chiri Sherpa, who climbed Everest 10 times, holding the record for the fastest ascent (under 17 hours), and for the most time on the summit without auxiliary oxygen (21 hours), as well as summitting twice in two weeks. He died on his 11th summit bid of Everest, falling into a deep crevasse in April 2001.

Among them is Scott Fischer, the American mountaineer and guide known for ascending the world’s highest peaks without extra oxygen. In May 1996 he led a group of clients up Everest, assisted by two other guides. After helping others, he summitted Everest late in the day and during his descent was caught in a violent blizzard that took the lives of 8 people, including Fischer. In this spot there is also a memorial to Anatoli Boukreev, a respected Russian Kazakhstani climber and one of Fischer’s fellow guides on that day. After rescuing others, Boukreev did manage to reach Fischer, but he was already dead. Boukreev survived, but was killed in an avalanche while climbing Annapurna 18 months later. One of the largest memorials is to Babu Chiri Sherpa, who climbed Everest 10 times, holding the record for the fastest ascent (under 17 hours), and for the most time on the summit without auxiliary oxygen (21 hours), as well as summitting twice in two weeks. He died on his 11th summit bid of Everest, falling into a deep crevasse in April 2001. From the memorial field, the trail descends through rock-strewn mayhem to the valley floor. The clouds build, settling on the peaks and draping everything in grey. The temperature drops. Porters toil their way up through the boulders under enormous weights bound for Base Camp. Angtu leads L carefully across an ice-bridge spanning the river, the pair of them slipping and dancing in unison, holding opposite ends of a walking pole.

From the memorial field, the trail descends through rock-strewn mayhem to the valley floor. The clouds build, settling on the peaks and draping everything in grey. The temperature drops. Porters toil their way up through the boulders under enormous weights bound for Base Camp. Angtu leads L carefully across an ice-bridge spanning the river, the pair of them slipping and dancing in unison, holding opposite ends of a walking pole. Over a rise they look down into the next valley, a steep-sided groove cut by a fast-flowing river. As they drop lower, the vegetation gets taller.

Over a rise they look down into the next valley, a steep-sided groove cut by a fast-flowing river. As they drop lower, the vegetation gets taller. She potters through the door curtain and climbs up onto the bench next to L. They stare at each other for a bit. She puts her face right up to L’s, and laughs. She pokes L. L smiles and pokes her gently back. She giggles and pokes. And giggles and pokes. And giggles. The soup arrives. Her mother shoos her off the bench. The little girl tries to climb out of the window, gives up and disappears back through the curtain. She makes herself busy in the yard throwing cups of water at hens.

She potters through the door curtain and climbs up onto the bench next to L. They stare at each other for a bit. She puts her face right up to L’s, and laughs. She pokes L. L smiles and pokes her gently back. She giggles and pokes. And giggles and pokes. And giggles. The soup arrives. Her mother shoos her off the bench. The little girl tries to climb out of the window, gives up and disappears back through the curtain. She makes herself busy in the yard throwing cups of water at hens. Lodge: The hot water bottles are free. Would you like some?

Lodge: The hot water bottles are free. Would you like some?

They cross the river below the village on a steel bridge strewn with prayer flags, and follow a wide path leading up to an open plateau. The sun streams from behind Ama Dablam’s peak, throwing it into silhouette and making the broad snow-field sparkle. Two other small groups, half a dozen trekkers each, are admiring the views back to Pangboche. L strides away across the plateau.

They cross the river below the village on a steel bridge strewn with prayer flags, and follow a wide path leading up to an open plateau. The sun streams from behind Ama Dablam’s peak, throwing it into silhouette and making the broad snow-field sparkle. Two other small groups, half a dozen trekkers each, are admiring the views back to Pangboche. L strides away across the plateau.

They walk towards the little cluster of expedition tents. A dozen or more people are standing or sitting in a group.

They walk towards the little cluster of expedition tents. A dozen or more people are standing or sitting in a group. L: I do actually. I’d really like to think so. The thing is, this landscape is just so enormous, and the weather and conditions up here are so powerful, that it makes one – well, me anyway – feel very tiny and at the mercy of my surroundings. And if you can’t control your environment, it’s instinctive to want to do all you can to stay on its good side.

L: I do actually. I’d really like to think so. The thing is, this landscape is just so enormous, and the weather and conditions up here are so powerful, that it makes one – well, me anyway – feel very tiny and at the mercy of my surroundings. And if you can’t control your environment, it’s instinctive to want to do all you can to stay on its good side. The way up to the 16thC Pangboche Monastery is lined with mani walls. Lots of them. D&L carefully pass them all to the left. Terraced fields are dotted with neat piles of manure and women are preparing the ground for planting potatoes. Pangboche is the oldest Sherpa village in the region, and this is its oldest monastery.

The way up to the 16thC Pangboche Monastery is lined with mani walls. Lots of them. D&L carefully pass them all to the left. Terraced fields are dotted with neat piles of manure and women are preparing the ground for planting potatoes. Pangboche is the oldest Sherpa village in the region, and this is its oldest monastery.

Despite the bustle outside, the elaborately decorated monastery complex is all but deserted. A dog lies flatly on the warm paving stones and four ponies amble through the grounds. D&L circle the gompa, spinning all the prayer-wheels, and admire the deceptively ancient-looking interior, dating back only to 1993. This monastery, originally founded in 1919, burnt down 70 years later and was carefully rebuilt. There is a beautifully serene Buddha, eyes half closed, meditating on the altar, and a wall of prayer books behind. They study a large painted wood panel.

Despite the bustle outside, the elaborately decorated monastery complex is all but deserted. A dog lies flatly on the warm paving stones and four ponies amble through the grounds. D&L circle the gompa, spinning all the prayer-wheels, and admire the deceptively ancient-looking interior, dating back only to 1993. This monastery, originally founded in 1919, burnt down 70 years later and was carefully rebuilt. There is a beautifully serene Buddha, eyes half closed, meditating on the altar, and a wall of prayer books behind. They study a large painted wood panel. L: Just look at them!

L: Just look at them! Descending from Namche to Lukla, they pass trekkers panting their way up the long ascent. In the valley fruit trees are bursting with white and pink blossom and the vivid green of buckwheat patchworks the fields. Rhododendron trees are in flower. They trail is teeming with trekkers and porters and donkeys and yaks.

Descending from Namche to Lukla, they pass trekkers panting their way up the long ascent. In the valley fruit trees are bursting with white and pink blossom and the vivid green of buckwheat patchworks the fields. Rhododendron trees are in flower. They trail is teeming with trekkers and porters and donkeys and yaks. The day dawns grey. It’s almost the only really overcast morning they’ve had in five weeks.

The day dawns grey. It’s almost the only really overcast morning they’ve had in five weeks. They wait, watching the runway through the window. Helicopters continue to arrive, fill and leave.

They wait, watching the runway through the window. Helicopters continue to arrive, fill and leave. They are back at the airport at 7am. The clouds are swirling, but higher, and the skies are much clearer. Planes arrive and leave. They check in again. Planes arrive. Planes leave. The cloud builds and lowers. The planes stop coming. They wait.

They are back at the airport at 7am. The clouds are swirling, but higher, and the skies are much clearer. Planes arrive and leave. They check in again. Planes arrive. Planes leave. The cloud builds and lowers. The planes stop coming. They wait.